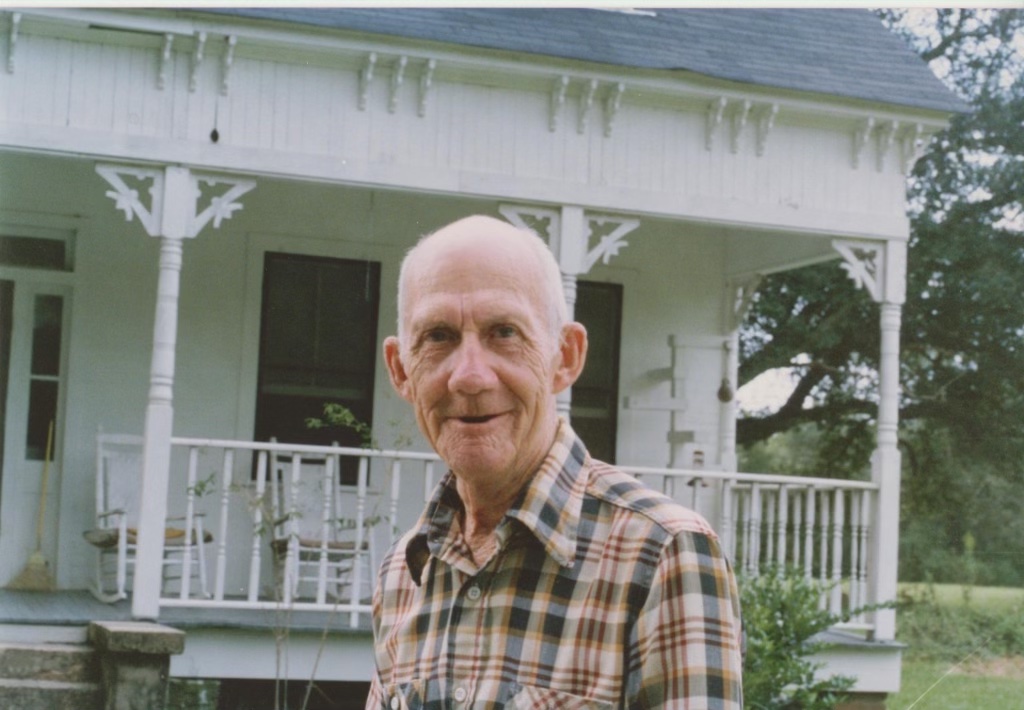

Homeplace of Emerson Lyle & Mary Victoria Phares Dunn

East Feliciana Parish

My paternel grandfather grew up in this house. It sat on LA Hwy 961, in East Feliciana Parish, between almost-to-Clinton and Felixville.

The house wasn’t completeted when my grandfather was born in the back room of the family store that sat out front near the road on the corner of the property. The store was long demolished before I could remember, and even before my father could remember.

Emerson Lyle and Mary Victoria Phares Dunn

The house was built in 1906 from heart pine lumber transported over dirt roads by wagon from the mill in Greensburg, more than 30 miles away. When I was a boy, my great-uncle “Buddy” and his wife Aunt Mary lived there. They were somewhat eccentric, like characters in a southern gothic novel. Uncle Buddy was skinny as a rail. Aunt Mary was his physical opposite — when she died, Charlet’s Funeral Home had to special order a casket for her.

My sister and I loved to visit with them back in the late 1980s. We figured they didn’t get many young visitors and we never knew what kind of stories, real or imagined, that we’d hear when we got there.

Aunt Mary’s bedroom was in the front of the house, behind the window there on the left of the photo. She stayed mostly in a reinforced queen-sized bed, dressed in a loose-fitting mumu. Uncle Buddy, or someone, used a hacksaw to remove the front of her tennis shoes so her feet could breathe. She kept a giant bottle of mineral oil on her nightstand , taking random swigs from it as she told stories. Aunt Mary was convinced that Martians were hiding in Washington, DC and that her brother-in-law, named Andrew but called “Scrub,” had been killed by the mafia because he had had a brief conversation with Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby when they passed through Clinton.

Uncle Scrub was the town drunk and he would sit on the bench outside the barbershop on Main Street in Clinton. When he got really lit, the sheriff or the deputies would let him sleep off his drunk in the jail, but one morning he was found hanged by his belt in the cell. Uncle Scrub’s death was officially ruled a suicide, but Aunt Mary, Uncle Buddy, and others swore that he was the target of a hit in the afermath of the Kennedy assassination.

Sometimes Uncle Buddy would be on the front gallery, reading his well-worn Bible. He could quote scripture like a tent revivalist. He wore the key to the Hepzibah Baptist Church on a chain around his neck. The church building is long gone, like the family store, but the cemetery remains, hidden beneath years of abandon and underbrush across the washed-out bridge that crosses Collins Creek.

Buddy standing in front of the gallery, 1992

The grave of his sibling stillborn twins is there, obscured now by an enormous pine tree. Another two of his brothers, Howard and Toler, are there, also. Howard died in 1912. He must have been so excited to get a horse for his 11th birthday. But the following day, the horse spooked and ran away with him. Howard was thrown against a clay bank, breaking his neck. Toler graduated from the Tulane School of Pharmacy. Haunted by crippling depression, he swallowed a full beaker of hydrochloric acid, killing himself at the age of 28. The family plot was once surrounded by an ornate, iron fence, but it too is now gone, stolen and sold by artifact hunters.

When we visited, the upstairs of the house hadn’t been occupied in decades. The middle dormer in the photo is the landing at the top of the stairs. The bedroom to the right was filled with cast-off things, including a sword from the Civil War that had belonged to one of my Confederate ancestors. The bedroom behind the left dormer, immediately above Aunt Mary’s room, fascinated me most. Here, my great-great-aunt, Sarah Katherine “Katie” Phares, died of tuberculosis in 1922.

Katie Phares (right) and her cousin Ophelia Dunn, circa 1910

The dark attic through the half-sized door at the other end of the landing held even more treasures. Piles of books from the 1850s through the 1920s, a marble-topped dresser, the scale from the store, a mahogany box doctor’s kit with tiny glass globes for bleeding, Toler’s pharmacy diploma from Tulane, and a giant steamer trunk filled with Katie’s scrapbooks, photographs, postcards sent by her friends and her brother Haden, Haden’s steel army helmet from WWI, and other personal effects.

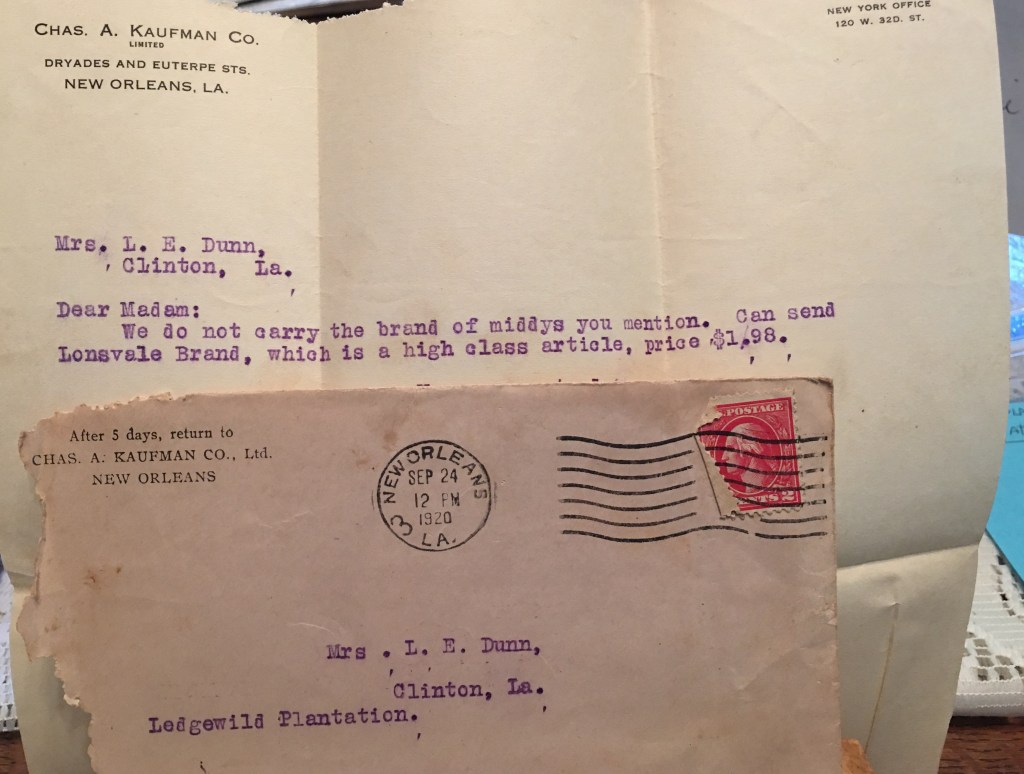

Also in the trunk was a letter addressed to Katie’s sister, my great-grandmother Mary Phares Dunn in 1920. It’s there that I discoverd that the big old house had a name.

Ledgewild.

On my last visit before Uncle Buddy died, he allowed me to take Katie’s belongings and a large number of books. They’re among my most treasured belongings.

When Aunt Mary died, Ledgewild was inherited by her son from a previous marriage, passing out of the family, and with it, the doctor’s kit, the scale, and Toler’s diploma. Uncle Buddy did not entrust them to me.

Several years ago, as I was driving through the countryside to take a photo of Ledgewild from outside the barbed wire fence that made it inaccessible, I audibly gasped to discover that it had been demolished. But when I look at this picture, I can still see and hear them.

Uncle Buddy and Aunt Mary in the bedroom to the left, just inside the front door.

Buddy & Mary with their dog Penny, 1992

So sad to learn that the beautiful home was demolished. We also have an ancestral home in the countryside near Erath in our family. I have photos and good memories of visiting the great aunt and uncle who lived there.

LikeLike